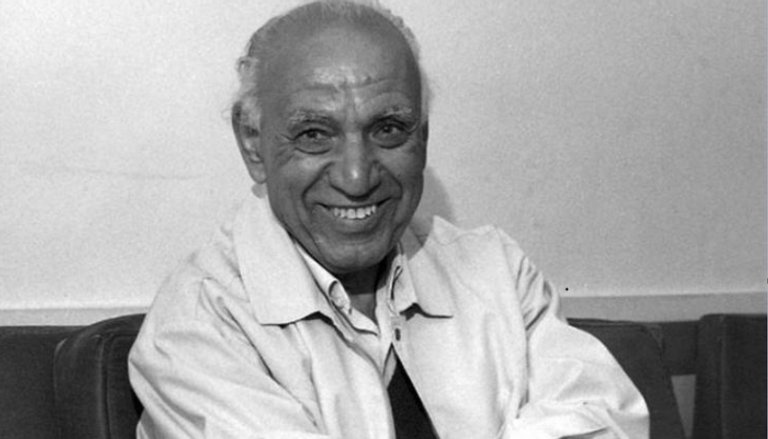

Director Salah Abu Seif is considered one of the pioneers of realism in Arab cinema. He represents a unique case that warrants careful study and reflection. Although he directed 42 films, he remained faithful to the current of realism he embraced—a directorial approach he cherished throughout his long cinematic career. He did not immerse himself in realism to the point of slipping into documentary, as many realist directors did after him. Nor did he push experimentation to the extent of falling into the trap of Westernization, as occurred with others, such as Youssef Chahine.

He was keen to maintain a balance between form and content—that is, between the film’s aesthetics and its thematic message. In this regard, he advised his students in an interview published on the website of the Arab School of Cinema and Television, stating:

“I ask you to uphold aesthetic values and understand that this does not mean falsifying reality. We are weary of ugliness in all its forms, presented under the pretext of realism. This is a grave misconception. Although reality consists of black and white, there are countless shades of gray between them, which allow the artist to choose among them to impart realism to their work—yet always after applying the aesthetic touch that initially captivates the spectator and draws them to watch the piece.”

On one hand, Abu Seif earned the appreciation of both critics and audiences. In addition to the numerous awards he received and the international festivals where he represented Egypt, Arab audiences adore his films to the extent that they memorize entire scenes, much like recalling a verse of poetry or a line from a beloved song. This is evidenced by the fact that even the average viewer can aesthetically read Abu Seif’s films, understanding the cinematic language through which he conveys the perspectives he wishes to express.

In this context, we cannot forget the iconic scene from the film (Cairo 30 - 1966) «القاهرة 30», in which Hamdi Ahmed is seated on a chair wearing a fez. In the background, two goat horns appear on the wall, positioned in the frame as if they are emerging from the head of his character, Mahjoub Abdel Dayem. This visually alludes to his immoral behavior, likening him to a goat that does not guard its honor.

In fact, the secret behind Abu Seif's popularity lies neither in the sophisticated cinematic language that appeals to critics nor in the excessive realism that draws audiences. Rather, it resides in the honesty inherent in his work and in the director’s ability to convey a point of view in a language that everyone can understand, without compromising the work’s aesthetic qualities. Ultimately, the film belongs to the realm of art, not of reality.

From this perspective, Abu Seif adopts a concept of realism that allows him to move freely, enabling him to present films like (The Second Wife - 1967) «الزوجة الثانية) or (A Woman’s Youth - 1956) «شباب امرأة», while also presenting an experimental film like (Between Heaven and Earth - 1959) «بين السماء والأرض» or a fictional film like (The Beginning - 1986) «البداية».

Abu Seif expresses this meaning by saying:

“Realism is realism in all films that are characterized by it. In my personal opinion, realism is to be honest in presenting your art to spectators. Alongside honesty comes the need to observe aesthetic values and mastery of the work. Above all, the artist must have a sound view from ethical and political standpoints, and must take into account, in choosing the subjects he deals with, that they be related to problems that concern all segments of the society in which he lives—problems that may extend to concern humanity at large.”

In Abu Seif's opinion, we can identify a very important issue: the relationship between art and ethics, or art and reality. Abu Seif places moral and political values above aesthetic values; he prioritizes content over form. This vision stems from his desire to present what matters to people, and even to humanity as a whole. I recall that in one of his television interviews, he expressed his desire to make a film about the issue of racial segregation, which is, of course, a fundamentally humanitarian issue.

The starting point of this committed cinematic approach can be traced back to the early beginnings of Salah Abu Seif, when he directed one of his first films, (Always in My Heart - 1946) «دايما في قلبي». About this film, he recounts a telling incident. The film was a romantic musical that included a love scene set in the Aquarium Grotto Garden. Abu Seif staged the scene with the young man sitting while the girl lay beside him on the grass. As a novice director, he was greatly impressed by the composition from a purely formal standpoint, paying little attention to the content of the scene or the meaning such an image might convey to the audience. It was only when one of the local working-class men—an uneducated “ibn al-balad”—remarked spontaneously, “Isn’t it shameful, sir, for a girl to lie next to a boy like that on their very first meeting?” that he became aware of the implication.

Abu Seif commented on this incident in a way that reveals the director’s humility in learning from the viewer, even if the viewer was not educated. He said:

“When I reflected on what this person said, I realized that the spontaneity of this ibn al-balad had drawn my attention to the fact that my focus on the composition and my great admiration for the form had made me overlook the meaning that could reach the viewer through this composition. In other words, I had given priority to form at the expense of content. I learned this lesson well and never made the same mistake again. I now give equal attention to both form and content, and I even prioritize content first, then attend to form afterward.”

In fact, Abu Seif did not completely abandon form in favor of content, but rather made it serve content. Advocates of art for art’s sake often object to this vision. In this respect, Abu Seif comes close to semiotic theorists, who treat the vocabulary of film as a linguistic space similar to natural language, such as Arabic and English, with its own rhetoric, grammar, and morphology.

The alphabet of cinematic language that Abu Seif relied on in his films consists of eight “letters”: five of which pertain to the image, and the remaining three to sound. The filmmaker must master these letters and master the expression of his artistic vision through their use. The five letters related to the image are: décor, actor, fixed props, moving props, and lighting. The three letters related to sound are: dialogue, music, and sound effects.

Although Abu Seif was influenced by Italian neorealism, which relies heavily on long takes, his long experience as an editor at Studio Misr led him to rely more on cinematic aesthetics derived from editing. In this context, Abu Seif distinguishes between two types of montage that he used in his films: parallel montage and intellectual montage.

An example of parallel montage is the scene he depicted in (Al-Fatwa - 1957) «الفتوة», which presents a comparison between the work of the film’s protagonist, Farid Shawky, as he pulls a vegetable cart, and that of a donkey performing the same task. Here, we see identical cuts on similar shots of the protagonist’s legs and the donkey’s legs, as well as the evident strain on both, suggesting that the protagonist is working like a donkey.

A similar scene can be found in (A Woman’s Youth - 1956) «شباب امرأة», where a comparison is drawn between Imam — played by Shukri Sarhan — who, with his strong and youthful body, rescues one of the workers who has fallen beneath the mill before he himself falls into temptation, and the donkey that turns the mill while blindfolded. Here, Imam’s physical strength is contrasted with the trap that Shafaat (Taheya Cariocca) will set for him, a trap he will walk toward like the blindfolded donkey, unable to see his way until he ultimately falls into it.

We also cannot forget the scene of luring and killing the victim in (Raya and Sakina - 1953) «ريا وسكينة». After the victim is drawn into the trap, the film cuts directly from the murder scene to the slaughterhouse, where the police are continuing their investigation into the ongoing killings. The cut lands on a shot of a butcher slaughtering a sheep — a stark visual metaphor indicating that the victim was slaughtered just as a sheep would be.

As for examples of intellectual montage, they are numerous, and what most distinguishes them is that they reflect Abu Seif’s moral convictions in filmmaking. From this perspective, they can be relied upon when theorizing any cinematic trend that seeks to prioritize practical ethics over artistic aesthetics — much like what happened when some coined the term “clean cinema,” a label launched without a convincing theoretical framework, relying only on good intentions and a call for virtuous morals.

In this regard, we find many scenes in Abu Seif’s films in which he was able to express the most intense human moments without falling into vulgarity or explicitness. One of the most striking examples is a scene from (The Boss Hassan - 1952) «الأسطى حسن», which depicts Zuzu Madi as an aristocratic lady who becomes attracted to Hassan, portrayed by Farid Shawky. She tries to seduce him and lure him into her bedroom. However, Abu Seif does not depict the intimate relationship explicitly. Instead, he substitutes it with a shot of a statue in one of the room’s corners that emits a whistling sound. In an earlier shot, the lady had explained to Hassan that the statue produces this whistling whenever it is “pleased.”

Through this detail, Abu Seif cuts to a shot of the two characters as they move toward the bedroom, followed by another shot of the statue as it emits a whistling sound. The final shot shows the statue beginning to whistle once more, serving as an indirect visual suggestion of the lady’s satisfaction resulting from their physical relationship.

A similar example can be found in a scene from (A Woman’s Youth) «شباب امرأة», in which intellectual montage is used to cut to a shot of a cannon firing in a generator, symbolizing the physical relationship between the protagonist, Shukri Sarhan, and the heroine, Tahia Carioca.

In any case, the genius of our great director cannot be reduced merely to his ability to employ cinematic language for moral purposes, but also encompasses his capacity to create innovative cinematic scenes. He drew attention to the fact that realism in cinema is not merely documentary-like; it is a form of artistic expression. He emphasized that the excessive use of cinematic language for its own sake can alienate the audience and compromise one of art’s most crucial functions: delivering a human message.