The Eve of the Announcement

On a bitterly cold evening, the frigid air seeped into my bones, sending shivers down my spine. I sought refuge in the farthest corner of my room, clinging to the warmth of the heater, and enveloped in a woolen blanket, though my feet remained exposed to the encroaching chill. My phone, clutched tightly in my hand, stayed connected to its charger. I believe it was a Sunday. On a wintry Sunday evening, my eyes drifted between drowsiness and reading. Twitter, now renamed ‘X’, rang with a notification that resonated in my ears like a tolling bell, preventing sleep from reaching my weary eyes.

But it was not the tolling of a Mass bell in the Italian city of Bologna, whose echoes could reach the horizons and even Melinde, where I resided in 2017. That would have been more logical than what I heard, especially since that day was Sunday, in a month of holidays. But that was not the case. Rather, that bell was a spherical hammer ringing out from Riyadh with the following news:

“Saudi Arabia announced permission to open cinemas and approved the issuance of licenses for those wishing to enter this activity, as the Board of Directors of the General Authority for Audiovisual Media, headed by Dr. Awad Al-Awwad, The Minister of Culture and Information, decided to issue licenses to those wishing to open cinemas in Saudi Arabia.”

Logical news according to the context of events— but logic does not prevail for someone who spent most of his life dreaming.

The Vanguard of Pioneers and Its Promises

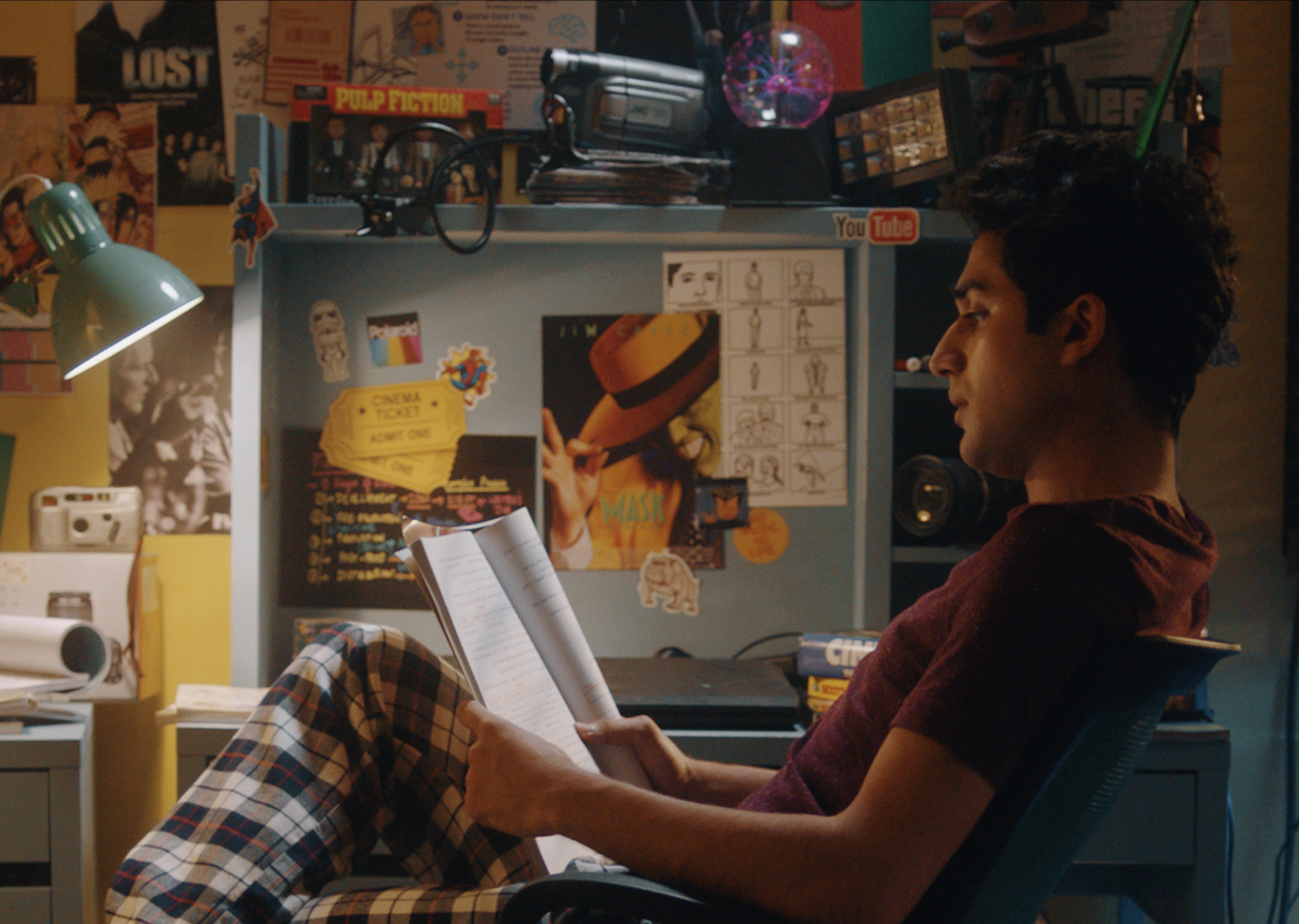

A decade has passed since Abdullah Al-Eyaf, who later became the head of the Film Commission, directed the film Cinema 500 km (السينما 500 كم). This film captured the yearning of generations who were inexplicably deprived of the illuminating glow of the rectangular screen. It also represented a generation that carried numerous Saudi stories close to its heart— stories it longed to share through that very screen.

I felt an immense surge of motivation as I witnessed the promises that accompanied that moment, akin to receiving a fragrant rose as a gift from a generation whose works I had grown up admiring from within the shadows. Their creations resonated deeply within me, as each comic tale they crafted felt like a reflection of my own experiences. These stories unfolded within a distinct space they had mastered— a space that was both personal to them and to me, existing outside the confines of traditional artistic authority and its restrictive norms.

What astonishes me, when I reminisce about those days, is the absence of controversy surrounding the legality of the decision. Instead, I encountered joyful expressions and a sense of amusement. All I witnessed during that time was an overwhelming passion. I wish I could have asked back then, “What is passion?”

The First Saudi Film

Several months had passed since the storm had settled, and everyone eagerly gathered behind the camera, waiting for the iconic clicker to signal the beginning. Yet, in their typical fashion, the Americans were swift to seize the commercial opportunity. They secured the first license to operate movie theaters in Saudi Arabia, choosing the King Abdullah Financial Center as their initial foothold in the Saudi market.

Boldly, they made grandiose promises, declaring their intention to establish forty theaters bearing their name within five years. While they did expand, reaching as far as Hafr Al-Batin and Jazan, they fell short of even reaching half of the exaggerated number they had boasted. Over time, those five years stretched into nearly six, as their ambitious plans struggled to fully materialize.

Despite my initial excitement, I can’t quite recall what was shown to us—the audience. However, there was a significant controversy surrounding the fact that the first film Saudis encountered, after long anticipation, turned out to be nothing more than an animated movie about emojis. It is as if they had eagerly waited to break their fast on a feast, only to be served a raw onion, as the proverb says. I am not even sure whether the film was ever actually shown. However, I vividly recall the moment a wave of ridicule washed over my face upon hearing the news. No emoji could ever convey my disdain. Even lengthy voice notes sent to the friend who had shared the news— and mocked my dreams— felt inadequate to capture the depth of my emotions.

Nevertheless, the superficialities and excesses of Hollywood held little interest for me. My heart, instead, yearned for the distant promise of a Saudi film— a longing that persists to this day. Yet, as the years pass, memories fade, leaving me with nothing but emptiness. I struggle to recall the first Saudi film to be documented and showcased in cinemas, but I do remember that the period of 2018-2019 was hailed by our generation as the year of the inaugural Saudi film, much like our ancestors named years after significant and extraordinary events: the Year of Mercy, the Year of Destruction— may God spare us from such trying times.

The question lingers— not only in my mind, but also in yours, and among experts in anthropology and history: Was the 2015 film Bilal (بلال) truly the first presented to us? It showcased remarkable advancements in illustration and animation technology and carried a compelling narrative at its core. Yet, curiously, I cannot recall how much discussion it sparked among people. Perhaps it was mentioned only in articles within our artistic press, which, true to its nature since the 1990s, seizes every opportunity to elevate any subject to great heights.

Or could it have been Shams al-Ma’arif 2020 (شمس المعارف) that took the spotlight as the inaugural production? This maiden offering from the Godus brothers drew substantial attendance and captured the attention of viewers of all ages, earning commendable critical acclaim. Alternatively, was it the presence of the renowned actress Hayat Al-Fahd and the constellation of Gulf screen personalities in the film Najd 2020 (نجد) that first graced our screens? Even their recurring appearances during the month of Ramadan were deemed insufficient by some, as they sought a more substantial presence within those cinema halls, viewing it as a golden opportunity to attain something—something they failed to fully achieve, in my estimation.

Or perhaps it was a movie that I never knew existed until the moment I penned this article. I dare say that it may have slipped under your radar as well, my brothers. Who among us could have fathomed that such a creation existed— let alone being aware of its actual producer? This enigmatic film, titled Farkash (فركش), according to the advertisements, emerged during my research for this piece. I stumbled upon an interview in Sayidaty Magazine in which the producer proudly announced the premiere of the first-ever film produced by a Saudi. Yet, to my surprise, it appeared the film had never been screened at all.

Instead, I discovered that it had been uploaded on YouTube for two years, with a rather intriguing title: ‘The Theft of the Film Farkash Before Its Theatrical Release’. Nevertheless, I must admit that it was an era shrouded in mystery, and I find myself inclined to overlook its realities with a clear cognitive bias.

From that perspective, I can confidently say that Shams al-Ma’arif was a commendable film and a promising start for the industry. Setting aside the repeated—and seemingly unjustified—shouting of Al-Shubaili’s character, portrayed from the perspective of an elementary school child, and the immaturity in the story’s structure. I believe it was an enjoyable film that signaled the beginning of a promising journey. It opened new horizons for a burgeoning market, even though its inception was marked by confusion as cinema sought to convey its message and fulfill its entertainment purpose. Unfortunately, unforeseen consequences would soon befall the people.

The Day the Pandemic Struck

On a day that one would not wish upon their worst enemy, the global economy was ravaged by the second iteration of the SARS-CoV virus—this time bearing the subtitle of a pandemic. People withdrew from conflict, choosing silence for fear of being stained by the blood of the innocent. It was a pandemic that displayed death tolls on a global counter, coldly enumerating the losses we endured. It spared no one. Fifteen million lives were added to the final tally, as if they were mere numbers we carelessly failed to account in our conversations.

All the Saudi films that had been a topic of discussion retreated into a hibernation—or vanished altogether—alongside those who bid us farewell. What was once shown in cinemas is now being sold to any unscrupulous platform, regardless of the meager price, leading to industry-wide losses stretching from China to Bahrain, and from Hollywood to Bollywood.

Projects were abandoned, and the sector’s economic viability was shaken in the eyes of entrepreneurs. Even those who proudly recounted their self-made success stories in establishing restaurants and cafes were hesitated to venture into this field—long regarded as one of the most enticing investments.

Perhaps the Egyptian model of the 1970s and 1980s stands as the best testament to this claim. Yet, the pandemic played by its own rules, and it seemed that no projects would emerge in the next five years without government approval and funding—an arrangement that, of course, implied further stagnation.

Dust, Unshaken by the Air of Change

After two years of apprehension and stifling silence that gripped us all, the time had finally come to pick up where we left off—this time facing even more daunting realities and challenges. The young individuals I mentioned earlier in this post at last received the long-awaited news of a strategic partnership with Netflix, spanning eight films with the potential for expansion. All the necessary elements are in place: financing, investment, reach, and expertise.

A tremendous wave, propelled by the winds of change, looms on the horizon, and within me hope persists and thrives. However, there are always individuals who remain impervious to the wind’s influence. They exist in every corner of our artistic history—people whose lack of understanding is perplexing, unable to decipher the signs of the times. The film Farkash, which I mentioned earlier, stands as a clear example, though I do not wish to confine this observation to a single instance. While it did not experience outright failure in the truest sense, there were others who embodied that failure—individuals I will discuss now.

The film No One Showed Up 2020 (لم يحضر أحد) (Or 123 Actions as indicated on the film’s poster) brought together a fusion of Levantine and Moroccan influences through the remarkable writing of Mrs. Maysaa Al-Maghribi. It featured the sons of the artists Mutreb Fawaz, as well as Lenin El-Ramly and Hijab Bin Nahit, alongside other social media personalities. Within this constellation of talent, Maysaa chose a role she believed suited her, showing her comedic prowess in a scene rich with paradoxes.

Unfortunately, the film turned out to be a miserable failure—more painful than the thirteen million spent on its production. After its release, Maysaa comically claimed that hired individuals intentionally sabotaged the film after receiving payment.

This situation raises troubling questions about the generation involved. Is it truly so difficult for them to perceive what is happening? Do they genuinely believe their annual screen appearances amount to success? Perhaps this misplaced confidence stems from the countless artistic newspaper articles—largely unread—that heap praise on series that supposedly upending conventions, public works that defy expectations, or the so- called screen-burning impact of one man’s creations and another’s shocking performances. While artists worldwide often display a measure of narcissism, its brazen exhibition on platforms subject to supply and demand find its clearest expression in commercial cinema.

I do not wish to focus solely on Maysaa as if she were solely responsible for the issue at hand, for the problem extends far beyond her. Let me now diverge from the linear narrative and shift to the present year, discussing what troubles me about the recent works of Mr. Muhammad Al-Issa. Unlike Maysaa, he had a busy period in Tash Ma Tash (طاش ما طاش), even if his efforts were overshadowed by the gloom cast upon us by the Saudi series of the third millennium.

These series seem endlessly fixated on portraying a large family living in a two-story villa, stumbling through supposedly comical situations. Muhammad Al-Issa concluded his career with the film Manahi 2 (مناحي 2) or (عياض في الرياض) if we go by the poster’s title, following the same theme, the same essence, the same bright, burning comedy. There seems to be an unwavering simplicity to it all, as if the world does not turn and time itself stands still.

Regardless, as viewers—no matter how childish or patriotic we may be—we cannot control the scene to bend solely to our desires, expressing only what we please. A diverse scene, encompassing both the good and the bad, is a healthy one, allowing each person to express their individuality. Yet, I often find myself perplexed by these individuals, unable to shake off the confusion they evoke.

An Abstract Film, Your Abstract Film

What once transpired in the days when we had no means to voice our dissatisfaction is now unfolding in broad daylight, regardless of our sentiments. Each person exists within their own bubble, and any opposing opinion is bound to provoke anger in a narcissist. The irony lies in the fact that this very narcissist once wrote critiques of giants like Ozu, Lynch, Kubrick, and Tarkovsky in a single night, back when they were as inexperienced as you. They felt entitled to criticize those titans in 2011, yet it somehow became forbidden for you— though you were part of the same group—to criticize their stance.

Instead, people started showering them with compliments out of fear of their wrath, even going so far as to write a lengthy article praising their incoherent film—one filled with random scenes and tedious frames—under the title: “A Saudi abstract film that offered a profound critique of ideology, a daring endeavor. In response to ontology.” However, a more fitting title would be: “A Saudi abstract film that tests our patience and compels us to leave immediately.” This is the kind of discourse that ought to prevail once the formalities are set aside.

What Happens in the Festival, Stays in the Festival

An educated artist seems unable to transcend their own bubble and effectively communicate with the audience. We find ourselves unable to grasp the language of their works, while a perplexing confusion persists around film distribution strategies. As a result, we have become the only ones who do not partake in viewing their productions. It’s as if what is created here is not intended for us at all, but rather for the global stage—much like Chinese athletes competing in the Olympics.

Saudi films travel across the world before being shown here, if they are shown at all. This raises a crucial question: what are we trying to prove by prioritizing global recognition over cultivating a genuine connection with our own audience? The reality is, there isn’t yet a strong local presence that fully satisfies or engages us, It feels as though there is a competition among Saudi directors to see who can grace the most Red-Carpet events as if that is the ultimate measure of success.

A Legislative Crisis

Speaking of what is red, I believe that the pandemic and its consequences are not what prevents the market from taking shape in the first place. Rather, the real issue lies in a clear gap in understanding the regulations and legislation—something we shouldn't overlook when discussing this matter. When I say that, what I see represents a lack of clarity in the regulations of the regulatory authorities for the recipient, or that there is something that hinders communication in these materials, I mean that there is a loose legal chain that can be interpreted differently from one person to another. It is precisely this ambiguity, overshadowing the current reality, that hinders the sector from being empowered in the way we aspire to.

Although we are witnessing qualitative improvement and constant modernization, I believe that, given we are still living in a transitional phase, faster development is still needed. My criticism does not stem from being a legal jurist or from having full awareness of what should be done, but rather from the perspective of the observer who sees that these materials are not always applied. Despite the similarity of circumstances and situations in many films, which simply means their ineffectiveness—or so my simple reading of them suggest— and the desperate need for improvement.

Commercial Failure

As we touch upon the observations of an observer, the most striking aspect of the current scene is its disheartening commercial failure. I have attended numerous films with anticipation, only to be met with empty theaters, leaving me burdened with a sense of isolation. The true cause of this phenomenon eludes me. It could be that the industry requires more extensive marketing efforts that go beyond traditional methods, such as relying solely on trailers. Perhaps, when promoting Saudi films, we need to explore additional avenues.

Moreover, it is disheartening to consider that the involvement of social media celebrities may merely serve as a desperate attempt to ease the cinematic loneliness one encounters when attending a movie. Likewise, reducing ticket prices for Saudi films could act as an incentive for people to show up. After all, it seems unlikely that a young individual who saves up to watch the latest Marvel spew would willingly allocate the same amount of money—or attention—to a Saudi film priced at a similar level. These are, admittedly, populist suggestions arising from my limited grasp of the economic landscape. Nevertheless, as an observer, I cannot deny the pressing reality of the commercial failure that looms over the industry.

The Platforms and Their Age

This failure is not unique to Saudi cinema alone, as it is a shared experience with the global film industry. We cannot remain isolated from the challenges faced by the world at large. The pandemic has further exacerbated the struggles that were already underway. Digital platforms have emerged as key players, not only serving as archives for global productions but also enriching their libraries with their own original content. They have become a form of home cinema in themselves. For Saudi cinema, this shift offers a pathway to attain commercial success, bypassing the daunting hurdles associated with ticket sales and distribution companies, which often generate embarrassing reports. Instead, the focus shifts to securing high viewership rates, the true extent of which is known only to the platform owners who place significant importance on such metrics. This arrangement serves as a motivating factor for watching the works, regardless of whether the reported viewership figures are accurate or not. While platform exposure allows for greater reach, it also contributes to a swift fading of the work’s presence in the collective memory. It is lost amidst the multitude of global productions available on the platform—a significant loss, indeed.We have a promising future aheadDespite the negative aspects highlighted by this discourse, the past five years have also witnessed encouraging progress. Films such as Zero Distance 2020 (المسافة صفر), Last Visit 2019 (آخر زيارة), The Tambour of Retribution 2020 (حد الطار), Forty Years and One Night 2021 (أربعون عامًا وليلة), Alhamour H.A. 2023 (الهامور ح.ع), and Raven Song 2022 (أغنية الغراب) have emerged as beautiful and promising productions. Despite the presence of problems and shortcomings, it is important to remember that perfection is an elusive concept. Endlessly analyzing films will never lead to complete satisfaction, and the ordinary or mundane does not negate its aesthetic aspects. While achieving the goal of perfect beauty may be challenging and even unattainable, I have no doubt that we will continue to progress towards it in due time.