For film critic Mark Peranson the true privilege of criticism lies in writing only about films and subjects that genuinely interest him—without feeling obliged to cover every new release. He writes largely on self-initiated pitches, focusing on artistic rather than industrial cinema, and treats criticism as a form of promotion—not in the commercial sense, but as a means of championing a film, an idea, or a filmmaker. For Peranson, the critic’s task is to foster understanding and engagement, opening pathways between the work and its audience.

Journey into Film Criticism

Peranson always wanted to be a writer. He began with fiction and several unpublished manuscripts before discovering that film could synthesize his interests in history and politics through a popular art form. His graduate dissertation explored the portrayal of prostitutes in Westerns, comparing cinematic representations with historical records and tracing the imprint of Victorian morality on the genre.

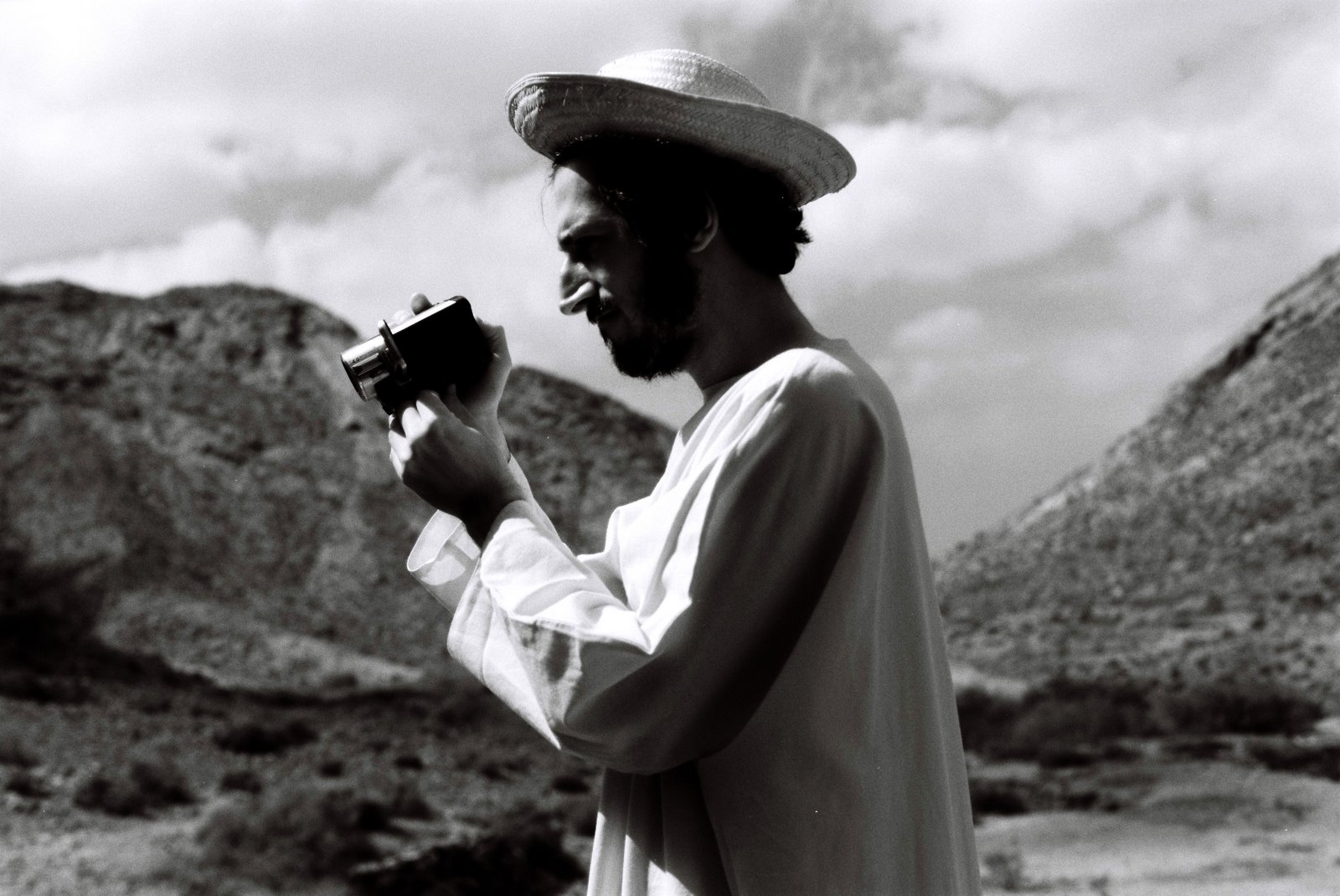

Although he never formally studied film or trained as a filmmaker, Peranson eventually made a few short films “by accident,” as he puts it. Still, he finds writing criticism far more efficient—a process of months rather than years, yet equally capable of artistic insight.

Essentials and Philosophy of Criticism

Peranson insists that good criticism begins with good writing. Mastering structure—of sentences, essays, and reviews—is, to him, the foundation of clarity and thought. A critic, he believes, should strive to offer original perspectives, steering clear of recycled opinions and conventional wisdom.

For Peranson, criticism transcends judgment; it is an act of interpretation and discovery, revealing new angles and emotional resonances. Yet he admits that producing criticism on a weekly basis can be challenging, as it risks repetition and fatigue in both language and thought.

Evolution and Influence of Film Criticism

According to Peranson, streaming platforms and new formats—such as virtual reality—have not fundamentally changed the language or approach of criticism, even though the contexts of viewing have diversified. He acknowledges that a critic’s opinions may evolve over time and avoids making definitive lists or rankings, noting that context and viewing situations can affect judgments.

He also recognizes that critics now hold less authority than before due to the proliferation of social media and the transformation of media landscapes. He explains that the influence of critics was traditionally limited to a core audience of cinephiles, whereas today it has become more diffuse but also potentially more democratic.

Saudi Film Industry and Advice to Filmmakers

Peranson is candid about his limited familiarity with Saudi cinema, yet he offers sincere encouragement to emerging filmmakers in the region. The most powerful films, he says, do not depend on large budgets but on authentic voices.

He advises young directors to discover the methods and models that fit their own realities and to prioritize personal expression over the pursuit of mass appeal. The Saudi film industry, he notes, is still in its early stages, producing only a handful of films each year—but it holds remarkable potential for growth and originality.